Medetomidine

View Medetomidine Webinar Recording here! (April 23, 2025)

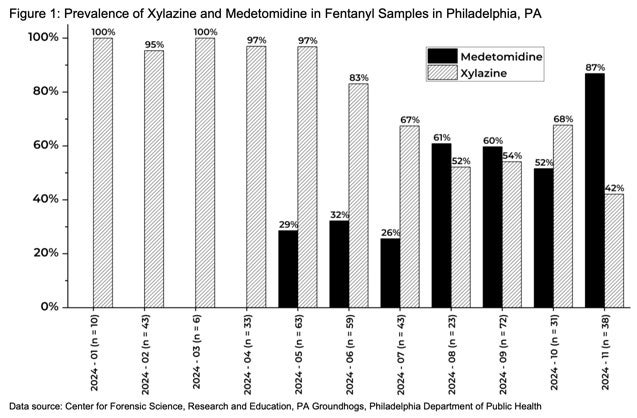

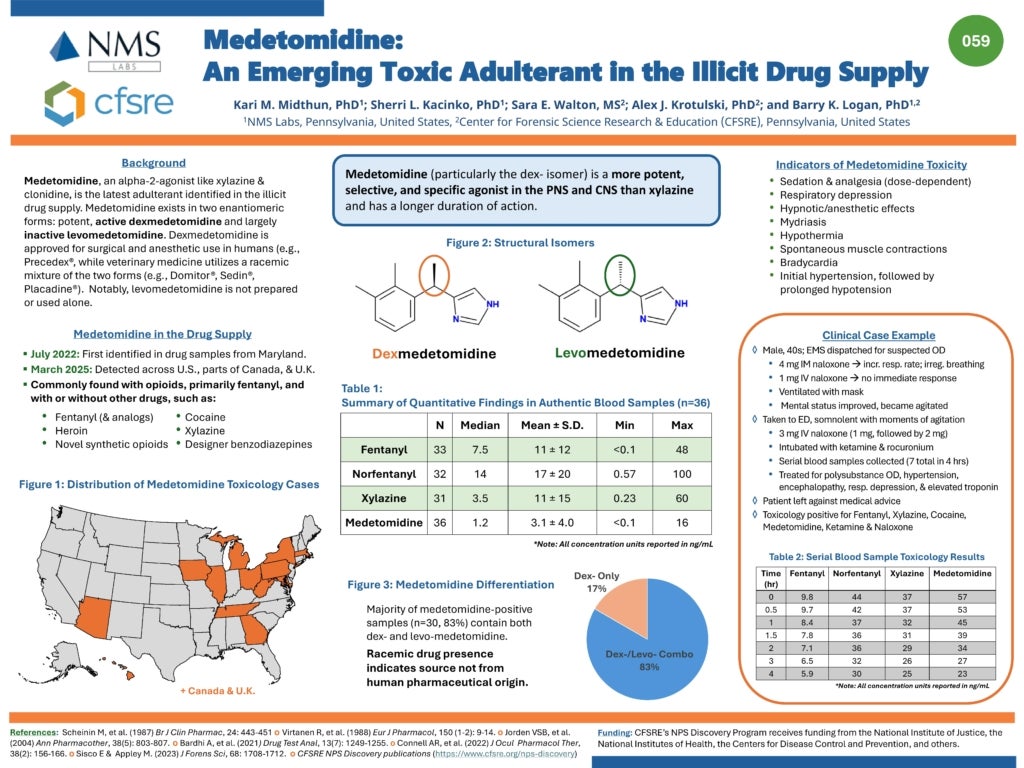

Medetomidine, an alpha-2 agonist not approved for human use, is an emerging drug adulterant that was found in 72% of illicit opioid samples by Philadelphia street drug checking programs in Q4 2024. During the same time frame, detection of xylazine (previously the most common adulterant), decreased from 98% to just 31% of samples. This represents a large shift in the regional opioid supply, one which has caused significant changes in the presentation of patients experiencing opioid overdose and withdrawal. It is important to note that fentanyl remained present in 100% of tested samples during this time period.

- used in veterinary sedation/analgesia

- an equal mixture of two enantiomers, dexmedetomidine and levomedetomidine (inactive)

- highly selective and potent alpha-2 agonist (100x more than xylazine)

- known to cause bradycardia and hypotension in animals

Medetomidine Overdose

Medetomidine was first noted to be clinically significant in a cluster of overdoses at several Philadelphia hospitals in Spring 2024. A case series from Temple University Hospital describes 11 patients who presented to the ED with opioid overdose and bradycardia of 50 beats/min or less. All patients tested positive for medetomidine. Details of these overdoses involving medetomidine can be reviewed below:

- 64% of patients received naloxone. Only one patient required naloxone to reverse respiratory depression, which was suspected to be an effect of fentanyl.

- All patients had sinus bradycardia without other conduction abnormalities

- Hypotension was uncommon, only seen in 18% of cases

- In the cases involving hypotension, vasopressors were not required and blood pressure normalized with IV fluids alone

- After reversal of hypoxia and respiratory depression, patients were noted to be persistently bradycardic with sustained heart rates below 50bpm

- Atropine was never required but was given once by EMS

- All patients tested positive for fentanyl, medetomidine, and xylazine

- Duration of bradycardia lasted from 1.5 h to 31.9 h (median 3.4 h [IQR: 2.7–9.3 h])

- There may be a relationship between medetomidine concentration and duration of bradycardia, though the small sample size has insufficient power to draw stronger associations

Medetomidine Withdrawal

Between September 2024-January 2025, an increasing number of patients presented to three health systems in Philadelphia with fentanyl withdrawal complicated by profound autonomic signs in the absence of benzodiazepine, barbiturate, or alcohol use. All patients needed inpatient hospitalization and the majority were managed in an intensive care unit (ICU). Nearly all required treatment with dexmedetomidine.

The syndrome parallels the onset and case descriptions of patients who develop dependence (or withdrawal from) the related enantiomer, dexmedetomidine, with a resultant rebound autonomic withdrawal syndrome.

Key components of this new drug withdrawal syndrome that is suspected to be secondary to medetomidine withdrawal include:

- severe hypertension and tachycardia (complications such as PRES and NSTEMI have been observed in some patients)

- intractable nausea and vomiting

- anxiety and agitation

- tremor without clonus or hyperreactivity

Importantly, these findings have been refractory to increasing doses of opioids (e.g. hydromorphone, methadone, oxycodone, fentanyl), sedatives (e.g. lorazepam, diazepam, midazolam, phenobarbital, propofol, haloperidol, droperidol), and adjunctive opioid and xylazine withdrawal medications (ketamine, clonidine, tizanidine, ondansetron).

A group of clinicians from Pittsburgh reported similar findings between October 2024-March 2025.

Clinical Recommendations for Managing Medetomidine Withdrawal

You can download our ICU medetomidine-fentanyl withdrawal management strategy here.

Recommended Medication Regimen (updated 9/11/25)

Note: Degree of alertness will influence regimen. Opioid administration should be prioritized.

(1) Long and short-acting opioid

Rationale: High quantities of fentanyl remain prevalent in the illicit opioid supply

(2) Dexmedetomidine (in lieu of clonidine)

Rationale: Drug checking reports a high prevalence of medetomidine in the illicit opioid supply

(3) Ketamine

Rationale: Regionally supported (addiction medicine) adjunctive in patients using fentanyl and/or xylazine

(4) Olanzapine

Rationale: Antiemetic and agitation treatment, may be particularly helpful in patients using xylazine and/or medetomidine

(5) Antihypertensive agents

Rationale: Severe hypertension may persist despite aggressive treatment with the above therapies. Earlier initiation is warranted if the patient has end organ dysfunction (hypertensive emergency).

(6) Additional adjunctive medications

References

de Andrade Horn P, Berida TI, Parr LC, Bouchard JL, Jayakodiarachchi N, Schultz DC, Lindsley CW, Crowley ML. Classics in Chemical Neuroscience: Medetomidine. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2024 Nov 6;15(21):3874-3883. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.4c00583. Epub 2024 Oct 15. PMID: 39405508; PMCID: PMC11587509.

Sinclair MD. A review of the physiological effects of alpha2-agonists related to the clinical use of medetomidine in small animal practice. Can Vet J. 2003 Nov;44(11):885-97. PMID: 14664351; PMCID: PMC385445.

https://hip.phila.gov/document/4874/PDPH-HAN-00444A-12-10-2024.pdf/

https://pagroundhogs.org/adulterants

Murphy L., Krotulski A., Hart B., Wong M., Overton R., McKeever R. Clinical characteristics of patients exposed to medetomidine in the illicit opioid drug supply in Philadelphia – a case series. Clin Tox. 2025 May; 1–4.

Huo S, London K, Murphy L, et al. Notes from the Field: Suspected Medetomidine Withdrawal Syndrome Among Fentanyl-Exposed Patients — Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, September 2024–January 2025. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2025;74:266–268. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7415a2.

Ostrowski SJ, Tamama K, Trautman WJ, Stratton DL, Lynch MJ. Notes from the Field: Severe Medetomidine Withdrawal Syndrome in Patients Using Illegally Manufactured Opioids — Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, October 2024–March 2025. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2025;74:269–271. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7415a3.

Centers for Disease and Control Prevention - Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR)

May 1, 2025

Notes from the Field:

Suspected Medetomidine Withdrawal Syndrome Among Fentanyl-Exposed Patients — Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, September 2024–January 2025

Our providers at Penn Medicine collaborated with partners at Temple Health and Jefferson University Hospital to illuminate the need for testing medetomidine in other regional drug supplies.

CDC Webinar: Medetomidine

Dr. Jeanmarie Perrone and Dr. Samantha Huo speak on the clinical implications of medetomidine mixed with opioids seen in Philadelphia and nearby region of Southeast Pennsylvania.

Practical Insights in Addiction Medicine

An ASAM Podcast Series called Practice Pearls

Drs. Stephen Taylor and Jeanmarie Perrone follow up on Season 1’s episode, “Emerging Illicit Substances: What Clinicians Need to Know.” Together, they discuss how medetomidine has continued to spread to different regions and what has changed over the past year. They explore strategies for managing medetomidine withdrawal, keeping patients safe, and preparing for this growing public health threat.

Listen to the full episode here.